Why amphibians are at risk ?

Amphibians have received much attention during the last two decades because of a now-general understanding that a larger proportion of amphibian species are at risk of extinction than those of any other taxon. Why this should be has puzzled amphibian specialists. A large number of factors have been involved, including most prominently habitat destruction and epidemics of infectious diseases; global warming also has been invoked as a causative factor. What makes the amphibian case so compelling is the fact that amphibians are long-term survivors that have persisted through the last four mass extinctions.

Paradoxically, although amphibians have proven themselves to be survivors in the past, there are reasons for thinking that they might be vulnerable to current environmental challenges and, hence, serve as multipurpose sentinels of environmental health. The typical life cycle of a frog involves aquatic development of eggs and larvae and terrestrial activity as adults, thus exposing them to a wide range of environments. Frog larvae are typically herbivores, whereas adults are carnivores, thus exposing them to a wide diversity of food, predators, and parasites.

Amphibians have moist skin, and cutaneous respiration is more important than respiration by lungs. The moist, well-vascularized skin places them in intimate contact with their environment. One might expect them to be vulnerable to changes in water or air quality resulting from diverse pollutants. Amphibians are thermal-conformers, thus making them sensitive to environmental temperature changes, which may be especially important for tropical montane (e.g., cloud forest) species that have experienced little temperature variation. Such species may have little acclimation ability in rapidly changing thermal regimes. In general, amphibians have small geographic ranges, but this is accentuated in most terrestrial species (the majority of salamanders; a large proportion of frog species also fit this category) that develop directly from terrestrial eggs that have no free-living larval stage. These small ranges make them especially vulnerable to habitat changes that might result from either direct or indirect human activities.

Living amphibians (Class Amphibia, Subclass Lissamphibia) include frogs (~5,600 currently recognized species), salamanders (~570 species), and caecilians (~175 species). Most information concerning declines and extinctions has come from studies of frogs, which are the most numerous and by far the most widely distributed of living amphibians. Salamanders facing extinctions are centred in Middle America. Caecilians are the least well known; little information on their status with respect to extinction exists.

|

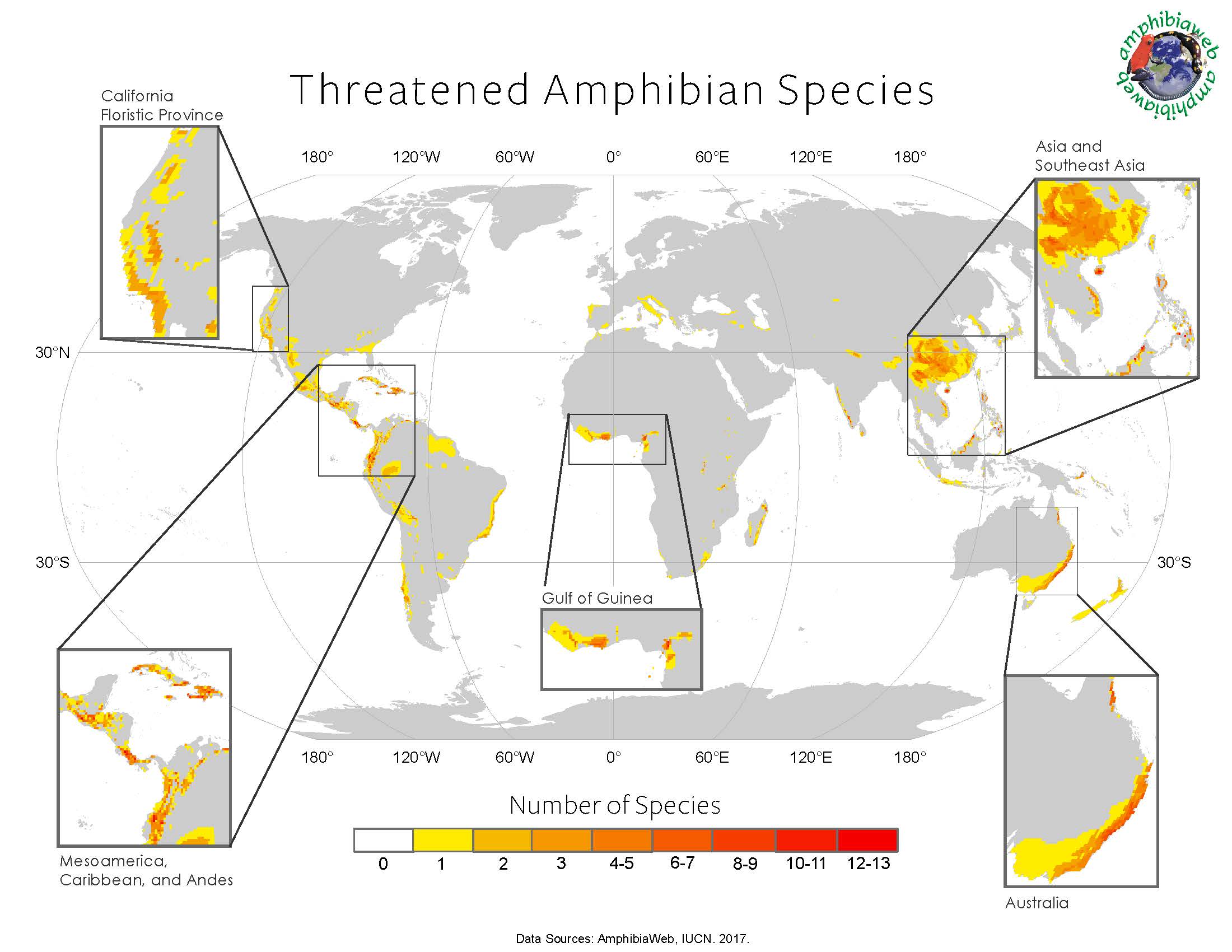

| A global map of threatened species highlights where the most vulnerable and endangered species are concentrated |

The Global Amphibian Assessment completed

it's the first round of evaluating the status of all then-recognized

species in 2004, finding 32.5% of the known species of amphibians to

be “globally threatened” by using the established top three

categories of the threat of extinction (i.e. Vulnerable, Endangered, or

Critically Endangered); 43% of species have declining populations. In general,

greater numbers, as well as proportions of species, are at risk in tropical

countries. Updates from the Global Amphibian Assessment are ongoing and show

that, although new species described since 2004 are mostly too poorly known to

be assessed, >20% of analyzed species are in the top three categories

of threat. Species from montane tropical regions, especially those associated

with the stream or streamside habitats, are most likely to be severely threatened.

Some important articles here-:

Amphibian Decline and Conservation in Central America

Comments

Post a Comment